edical artist is certainly not an everyday job. Nevertheless, medial illustrations are an important tool in science. With her work, Pascale Pollier tries to "push against the boundaries of our knowledge and social acceptance."

How would you explain the difference between a medical artist and a medical illustrator?

It is a very fine line, as they originate from the same source, but it is the difference of intention that distinguishes the one from the other. A medical illustrator is trying to communicate complex scientific findings through skills learned over many years of study. As medical illustration is seen as a functional educational art form, and the main aim is to be precise and clear and explanatory, the artistic expressive freedom is sometimes a little limited. A medical artist would seek to capture a more philosophical, sometimes even political, communication, and must feel free to express these findings in any way found to be suitable. The distinction is made by the philosophy of the activity itself.

Where does one find medical art?

Medical illustration can be found in medical educational books, explanatory surgery books, hospital leaflets, posters, educational medical 3D models, teaching aids, courtrooms, forensics, facial reconstruction, etc.

Medical art can be seen in many museums, galleries and exhibitions. In fact, it could be said that a great deal of recent art has some reference to things medical or scientific within its symbolism. Medical art in the contemporary art world has become more and more popular of late, almost a fashion trend. Some artists could even be accused of jumping on the bandwagon of art/science, as it has become so popular. Sad to say, sometimes the lack of knowledge and research can let the movement down a little.

How would you describe the purpose of medical art?

It is one of the ways out of the cul-de-sac that Modern Art found itself in at the turn of the century.

By returning to serious scientific and anatomical study, doors have opened to a new discipline altogether. This is enhanced by the arrival of new technologies, breakthroughs in physical science and the wealth of new materials now available. The future is once again very exciting. It’s a great time to be an artist and nobody has much of an idea where this will lead.

What skills are necessary for a medical illustrator?

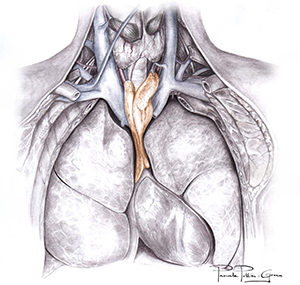

A medical illustrator needs great passion for medicine and an understanding of complex scientific concepts, and the talent to then translate these concepts in a visual manner. Of course, one has to be a talented draftsperson and be creative in executing the artwork, but the main thing is the communication and the depiction of the anatomically and scientifically correct information.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to become a medical illustrator?

Take direct observations from the source, study from the cadavers, go to dissection rooms and operations, get reference materials and take notes, talk to the scientists and get the facts right.

Are the same skills and steps necessary for becoming a medical artist?

Most certainly yes! Either visually or philosophically, one has to get the opportunity to absorb and relay the impressions of being confronted with one’s own mortality. This can only happen when one goes to the source and experiences these impressions directly.

Does your work require more scientific or artistic background?

It is a perfect mixture of both, really a melding of art, science, philosophy and technology.

How do you create your work?

The inspiration for my sculptures always comes from direct observation, never compromising my scientific integrity for an artistic effect. Anatomical correctness was and remains of the utmost importance to me, entwined with the desire to capture complex life issues. What follows is the attempt to communicate these philosophical debates in a visual manner.

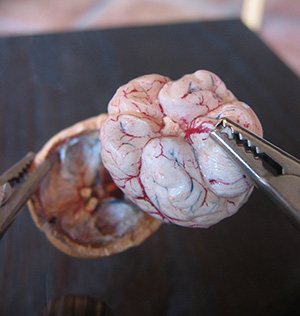

An example of this is "Autopsy in a Nutshell", mixed media, 30 × 30 cm, 2006. This work was created after witnessing an autopsy. I witnessed a brain being removed from the skull and it was placed into my hands for observation. This experience made a profound impression upon me. Holding this young man’s brain, which contained all the experiences of his life, was very humbling. The magnifying glass in this sculpture represents the observer.

The size of the brain and the reference to the walnut was dictated by the desire to highlight the link to nature and the micro-macro cosmos, all of which is interconnected and beautifully synchronized. My sculpture was featured in an article by Martin Kemp in Nature.

How closely do you as an artist collaborate with scientists?

I work directly with scientists most of the time. With BIOMAB, we organize dissection drawing classes at the University of Antwerp. From these meetings, I create a great number of my notes and reference drawings for projects that I am working on for new sculptures or films. I have access to medical laboratories, dissection rooms, autopsy theatres, hospitals, operating theatres, and medical anatomy and pathology museums. I discuss my concepts and ideas for new works with as many relevant scientists as I can, and in many cases we collaborate on these projects.

We could imagine that you are sometimes faced with difficult decisions; for example, must you sometimes sacrifice some scientific accuracy for the sake of art? How does this potential area of conflict (scientific accuracy versus art) affect your work and the way you think about it?

My artwork always stems from direct observation and research. I try not to compromise my scientific integrity for an artistic effect.

Medical illustrators, however, sometimes have to emphasize certain structures, to clarify complicated scientific concepts, and thus they have to take things out of context so the perspective and proportions change accordingly. The same is true of medical art in that in order to map out the essence of the human body, an abstraction is sometimes needed. This is true of all maps, including geographical. An example that springs to mind is the simplified map of the London underground, which was designed by Harry Beck in 1933. It is an image we all accept and use every day and is a clever abstraction of the complex reality.

This is a very delicate but important point. The artist and the scientist must begin their days with no preconceptions about the possible outcome of their research. They must be open to all ideas, including the supposedly ridiculous and impossible. They must empty their heads of all previous knowledge and journey forth with the innocent vision of a child. All preconceptions limit the ability to see clearly. If the outcome of research is pre-empted in any way, it will be subservient to expectation and therefore flawed. The open mind is the greatest tool of all faculties.

Do you ever find you have to justify your work as an artist towards scientists? If yes, how do you do this?

I like to get my work approved by scientists whenever possible. While creating the work, I ask for feedback and information before I publish or exhibit. I always try my best to get the scientific information across accurately through lots of research and cross referencing from different reputable sources.

I sometimes wonder if some scientists truly acknowledge the importance of medical art, and I feel that it is possibly a lifetime’s work for this new field to prove itself as a valuable discipline. We who are involved and fascinated by this amalgamation are in no doubt of its worth and potential benefit to art and science.

Some might see a contradiction between the sciences and art. How do you see this?

The common goal between art and science is quite simply the business of looking and questioning. In many ways, science has gone so far into abstract thought processes that it has become an art form, and in some cases has left art behind with the depth and strangeness of modern physics and mathematics. Physicists now sit around in cafes like artists from the 19th century, discussing their theories and saving time by talking and learning from each other’s research. Many theories in science can no longer be proven, so conjecture and a kind of faith in research alone is what keeps them going. The two faculties have grown together without any external encouragement.

What do you hope to achieve with your work by bridging art and science?

That’s a very big question. To answer it, you must excuse me if I go a bit over the top.

Everything is possible. I believe that only by breaking down the boundaries between all faculties is man going to move forward. Science on its own would become so abstract that the people would be left behind. There is a new renaissance happening, and our duty is to be a part of it. The future is ours only if we move with it. The restrictions people put upon themselves isolate them in an ivory tower are going to destroy us in the distant future. Collaboration, open mindedness, passion to understand and energy to learn from each other is the way forward.